Deciphering Low-Level Helicobacter pylori

A Case of Clinically Significant Low-Level Helicobacter pylori

The Gastrointestinal Microbial Assay Plus (GI MAP™) tests for H. pylori using quantitative PCR. The assay is extremely sensitive, detecting H. pylori at as little as 10 organisms per gram of stool. Because the organism is quantified, the test can report the concentration of H. pylori instead of simply a “positive” or a “negative” result. The laboratory has set the reference range as < 1e3 (1000) organisms per gram of stool. Below this level, however, it is still possible for H. pylori to be problematic. This case will review some of the criteria used to determine clinical significance below the reference range.

Low-Level H. pylori: To Treat or Not to Treat

One of the strengths of the GI MAP is that it detects Helicobacter pylori with great sensitivity. However, the ability to quantify just 10 organisms per gram means that Helicobacter pylori will be detected at low levels that may not be clinically relevant.

Helicobacter pylori is estimated to be present in roughly 50% of the human population but will only cause disease in roughly 15% of those cases. There is evidence that Helicobacter pylori can modify the human immune response to confer protection against certain conditions such as asthma, eczema, IBD, diabetes and obesity. Whether Helicobacter pylori acts as a pathogen or a symbiont will depend on complicated bacterium-host interactions. The art, then, comes with determining which cases of positive Helicobacter pylori deserve treatment.

Decision to treat low level H. pylori will be personal, aligning clinical decision making and patient values. Some clinicians will choose to treat H. pylori every time it is present, while others will only treat when it is out of range. Still others will only treat when virulence factors are present.

Considerations When Assessing Low-Level H. pylori

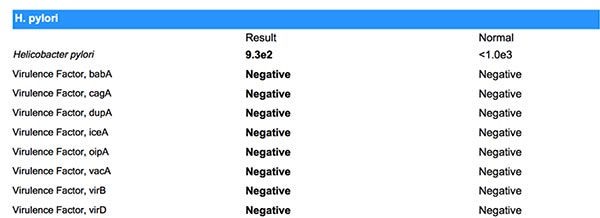

Virulence Factors

Virulence factors are genes that may be found within the genome of H. pylori. These genes are related to higher incidence of pathology such as gastric or duodenal ulcers and, rarely, gastric carcinoma. If these genes are present, H. pylori will be significant for treatment regardless of level. More information on virulence factors can be found in the GI MAP White Paper.

Upper Gastrointestinal Symptoms

When assessing a case of low-level H. pylori, upper GI symptoms such as gastritis and reflux should be considered. The presence of these symptoms may indicate significant H. pylori infection, even in the context of low-level stool H. pylori.

Downstream Effects of H. pylori

To adapt to the low pH of the stomach, H. pylori can produce urease which neutralizes the acid. If concentration of H. pylori is high enough, this may significantly affect gastric acidity, resulting in hypochlorhydria. This can contribute to significant effects such as lower esophageal sphincter dysfunction, digestive insufficiency, dysbiosis, and nutrient malabsorption.

Signs to monitor in clinical history include: evidence of poor nutrient absorption, fatigue, immune deficiency, bloating, and indigestion.

Findings to look for on the GI MAP include widespread dysbiosis and low elastase-1.

Personal History of H. pylori Infection

If H. pylori is detected despite history of herbal or antibiotic treatment, this is incredibly significant. Current treatment plan should be adjusted to include agents to modify treatment resistance.

Other Considerations

- Not all cases of H. pylori will require antibiotic therapy

- H. pylori is more likely to be significant as concentration approaches the reference range

- Antibiotics are not always needed. Botanical preparations have excellent safety profiles and show promise in treatment of high- and low-level H. pylori.

- If one member of a household is being treated for H. pylori, it may be reasonable to test and treat the other members of the household (or others in proximity)

- Treatment of low-level virulence-negative H. pylori is not urgent

Case Summary

AS, a 36-year-old female of South Asian descent, presented in office with a 6-month history of severe upper abdominal pain accompanied by constipation and bloating. She also reported fatigue, hair loss and severe premenstrual mood changes, heavy, painful menses with clotting. AS presented with GI workup, including full colonoscopy. She had not had an upper endoscopy. On questioning, she revealed that she had a history of positive H. pylori, which was treated with two rounds of antibiotics. Protocols were unknown.

She also provided previous lab results. All findings were normal except for high ANA titers, alternating high and low ferritin and persistently low mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH).

Initial Workup and Rationale

To rule out causes of fatigue and hair loss:

- Thyroid assessment – TSH, T3, T4, anti thyroperoxidase, anti thyroglobulin

- Auto Immune Markers – Anti-nuclear antibody (repeat), rheumatoid factor, anti-dsDNA, ENA

- Hemoglobin electrophoresis – this is not part of routine assessment but given the patient is of South Asian descent and has chronically low MCH, this test was run to rule out thalassemia.

To assess gastrointestinal health and rule out H pylori:

- GI MAP Stool Test

Findings from the Serum Testing

- Thyroid normal and in optimal functional range

- ANA titers high

- Positive alpha thalassemia trait

- GI MAP results as below

Assessment of the GI MAP

The test is negative for pathogens, fungi/yeast, viruses and opportunistic parasites.

H. pylori

H. pylori is detected at 9.3e2 (930 organisms) and is negative for virulence factors.

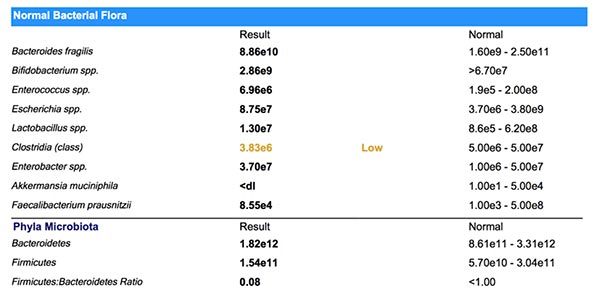

Normal Flora

The normal flora show two anomalies: Clostridia class and Akkermansia muciniphila, which are both deficient. Deficient clostridia can be associated with inflammation and auto-immunity. Akkermansia muciniphila is a mucus-loving organism that thrives in a healthy gut terrain. Deficient Akkermansi can often signal a compromised gut lining or intestinal permeability. Both findings correlate well with clinical history in this case.

Opportunistic Bacteria

The opportunistic bacteria show a common pattern of mild growth, often suggesting digestive insufficiency. On this test, we see overgrowth of Bacillus spp., Enterococcus faecium and Streptococcus spp. There is also unexpected growth of Enterococcus faecalis and Klebsiella pneumoniae. Klebsiella pneumoniae has the potential to be problematic in this case. The test reveals a small population of this organism but, if left unchecked, Klebsiella pneumoniae can be a potent auto-immune trigger and histamine producer.

Methanobacteriaceae, Prevotella spp. and Fusobacterium spp. are expected findings on the GI MAP. The levels found here are unremarkable.

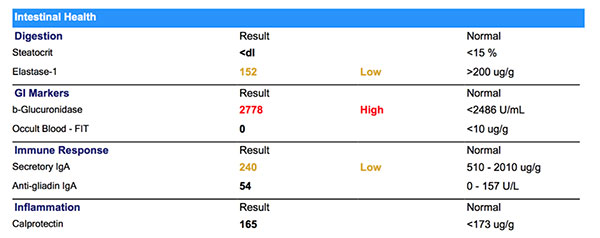

Intestinal Health

Steatocrit is normal, while elastase-1 is deficient. Low elastase is a common finding secondary to significant H. pylori infection.

ß-Glucuronidase is commonly found high in cases with bacterial overgrowth. In cases with significant hormonal symptoms, this can be a very significant finding since ß-glucuronidase can contribute to increased levels of circulating hormones.

Occult blood is negative.

Secretory IgA is low, which can be multifactorial. In this case nutrient deficiency, reduced mucosal health and chronic stress are likely to be be contributing to low Secretory IgA.

Anti-gliadin IgA is unremarkable.

Calprotectin is within range, but higher than the functional range of < 50ug/g. This value is likely to be attributed to the dysbiosis and immune dysregulation in this case.

Impressions

After careful review of the GI MAP and clinical history, the H pylori was determined to be significant for treatment based on the following criteria:

- Overgrowth of opportunistic bacteria

- Low elastase-1

- Significant upper GI symptoms

- Positive ANA titers

- Past history with H. pylori infection

Other goals of treatment include: strengthening digestion, de-activating ß-glucuronidase, nourishing enterocytes, supporting normal red blood cell and increasing production of hemoglobin.

NOTICE: Information provided by Diagnostic Solutions Laboratory does not constitute medical advice; but is for educational purposes only.

Initial Treatment Plan

- Mastic gum 1500 mg daily Deglycyrrhized licorice 225 mg daily* Zinc Carnosine 112.5 mg daily

- Green Tea daily

- Oregano Oil – 150 mg daily

- Digestive Enzymes without HCl

- Calcium-D-Glucarate 450 mg daily

- Antioxidant Formula: NAC, ALA, CoQ10, Vit C, Vit E, Selenium

Follow-Up

7 Days

After one week, constipation had completely resolved. Upper abdominal pain and bloating remained but had decreased in frequency and intensity.

21 Days

After three weeks, patient reported relief from upper abdominal pain and bloating had decreased significantly. Energy was markedly increased.

60 Days

At two month follow up, patient reported diminished hormonal symptoms. Mood was reported as more balanced throughout the month, with one to two days of decreased mood before menses. Menses was lighter and clotting was rare.

Treatment Adjustment at 60 days

Discontinue

- Mastic Gum

- Oregano Oil

Continue

- Zinc Carnosine

- DGL

- Green Tea

- Digestive enzyme

- Antioxidant formula

Introduce

- Probiotic 50 billion CFU daily

- L-Glutamine

Follow-Up Plan

Six weeks post-treatment, a standalone H. pylori Panel will be run to determine success of treatment. The next round of treatment will be based on this test result.

Discussion and Free Webinar Resources

The decision to treat low-level H. pylori requires careful consideration of multiple factors. Clinical history and test results should be analyzed to determine whether detected H. pylori will be significant for treatment. If H. pylori is deemed significant, botanical preparations may be very safe and effective options for the treatment of low-level H. pylori and may be a reasonable substitute for antibiotic therapy.

Amy Rolfsen, ND

Amy Rolfsen, ND, is a distinguished naturopathic physician, seasoned speaker, and dedicated medical educator renowned for her specialization in the intricate realm of the gut microbiome and gastrointestinal health.

In addition to her role at Diagnostic Solutions Laboratory, Dr. Rolfsen operates a thriving private practice, where she extends her services through virtual consultations specializing in lab interpretation, complex gastrointestinal conditions, and pediatric care.

The opinions expressed in this presentation are the author's own. Information is provided for informational purposes only and is not meant to be a substitute for personal advice provided by a doctor or other qualified health care professional. Patients should not use the information contained herein for diagnosing a health or fitness problem or disease. Patients should always consult with a doctor or other health care professional for medical advice or information about diagnosis and treatment.

References

- Chu, Y. T., Wang, Y. H., Wu, J. J., & Lei, H. Y. (2010). Invasion and multiplication of Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial cells and implications for antibiotic resistance. Infection and immunity, 78(10), 4157-4165.

- Dubois, A., & Borén, T. (2007). Helicobacter pylori is invasive and it may be a facultative intracellular organism. Cellular microbiology, 9(5), 1108-1116.

- Fahey, J. W., Haristoy, X., Dolan, P. M., Kensler, T. W., Scholtus, I., Stephenson, K. K., ... & Lozniewski, A. (2002). Sulforaphane inhibits extracellular, intracellular, and antibiotic-resistant strains of Helicobacter pylori and prevents benzo [a] pyrene-induced stomach tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(11), 7610-7615.

- Kronsteiner, B., Bassaganya-Riera, J., Philipson, C., Viladomiu, M., Carbo, A., Abedi, V., & Hontecillas, R. (2016). Systems-wide analyses of mucosal immune responses to Helicobacter pylori at the interface between pathogenicity and symbiosis. Gut microbes, 7(1), 3-21.

- Lai, L. H., &Sung, J. J. (2007). Helicobacter pylori and benign upper digestive disease. Best practice & research Clinical gastroenterology, 21(2), 261-279.

- Medina, M. L., Medina, M. G., Martín, G. T., Picón, S. O., Bancalari, A., & Merino, L. A. (2010). Molecular detection of Helicobacter pylori in oral samples from patients suffering digestive pathologies. _Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Buca_l, 15(1), e38-42.

- Necchi, V., Candusso, M. E., Tava, F., Luinetti, O., Ventura, U., Fiocca, R., ... & Solcia, E. (2007). Intracellular, intercellular, and stromal invasion of gastric mucosa, preneoplastic lesions, and cancer by Helicobacter pylori. Gastroenterology, 132(3), 1009-1023.

- Oh, J. D., Karam, S. M., & Gordon, J. I. (2005). Intracellular Helicobacter pylori in gastric epithelial progenitors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(14), 5186-5191.

- Polk, D. B., & Peek, R. M. (2010). Helicobacter pylori: gastric cancer and beyond. Nature reviews cancer, 10(6), 403-414.

- Smyk, D. S., Koutsoumpas, A. L., Mytilinaiou, M. G., Rigopoulou, E. I., Sakkas, L. I., & Bogdanos, D. P. (2014). Helicobacter pylori and autoimmune disease: cause or bystander. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG, 20(3), 613.

- Tong, J. L., Ran, Z. H., Shen, J., Zhang, C. X., & Xiao, S. D. (2007). Meta‐analysis: the effect of supplementation with probiotics on eradication rates and adverse events during Helicobacter pylori eradication therapy. Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics, 25(2), 155-168.

- Yamaoka, Y. (2010). Mechanisms of disease: Helicobacter pylori virulence factors. Nature reviews Gastroenterology & hepatology/, 7(11), 629.__